After

the Turbocore, there is a dynamo (or as we call it these days, a permanent

magnet generator). The generator that is

attached to the Turbocore produces electricity at 1 kHz, much too fast for conventional

equipment to use it, so we pass the power through a rectifier to make stable DC

power across a DC link. After the DC

link, an inverter changes the power to a more standard form of AC power – in this

case 60 Hz standard utility power - so that it can go into the grid, power a

compressor, power a beam pump, or be used for other applications. A DC converter could also be installed in

lieu of the inverter for DC applications.

This is a typical power conversion architecture

for microturbines.

While

this architecture is a little more complex than your household Honda generator,

it gives us product flexibility and reliability. The DC link is electrically simple, and is a

good place to create modularity in the engine.

Components on the left can be changed independently of components on the

right. This means it’s easier for us to

cost effectively provide 120V 1-phase power or 3 phase 240V power or even 48

VDC by changing a few parts. On the

other side of things, it’s easier for us to make upgrades to the underlying

hardware—the engine and the generator—without sacrificing electrical

quality. In fact, multiple inverters and

multiple generators can be attached to both sides of the link, providing end

users with a wealth of options for power.

While

we are talking about electrical, and what that means for the end user, we do

want to talk about why the Dynamo Turbocore has two turbines. We could have gone with a single turbine:

it’s cheaper, there are less parts and less engineering to be done with a

single shaft engine. However, we went

with a split shaft design because we realized doing so would result in a more

stable and more reliable engine whose performance would be less sensitive to

changes in the application.

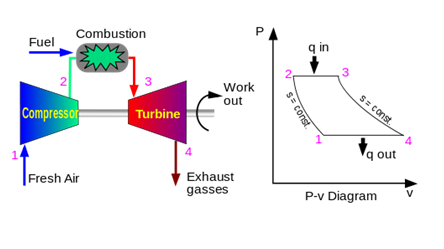

A

two-shaft engine has two main subsystems: the gas generator and the power

turbines. The gas generator includes the

compressors, the combustion chamber, and the turbines that power the

compressors; the remaining turbines are mechanically connected to an electric

generator and are called power turbines.

There are three main advantages for doing this.

The

first advantage of a two-shaft engine is that the second turbine, which spins

the electric generator, can be designed to operate at a lower RPM, which

results in less stringent performance requirements for the turbo-machinery, the

electric generator and the power conversion unit. This

holds true for mechanical loads as well, which also see significant advantages

from lower gear ratios and lower speeds.

The

second advantage is that the power turbine is a constant power device, which is

exhibited as a significantly superior torque characteristic versus engine speed

compare to a single-shaft engine. For a

single-shaft engine, the available torque decreases to zero as the speed of the

engine drops; for a two-shaft engine, the available torque increases as the

speed decreases. The torque

characteristic for a two-shaft engine t is also superior to that of a

reciprocating engine, which has a relatively flat torque curve. The torque advantage is important during back

starting heavy loads.

Lastly,

the Turbocores are controlled to provide consistent power to the power turbine;

the gas generator is essentially de-coupled from the power demands; the gas generator can be throttled up and

down faster and the compressor is not limited by the load on the turbine, and

can generally operate near their efficiency point. The control system can be more robust—there

is less compromise between keeping the engine operational and preventing a

brown-out. Big power generating turbines

where the load varies over time are generally of this split shaft configuration. As a corollary split shaft engines are easier

to start, with less thermal loading to the turbine system.

It

is for these reasons and others we went to a split shaft design for our

Turbocore product.